Factor investing refers to specifically targeting independent risk factors in securities markets that explain the differences in returns between diversified portfolios. Here we'll look at what factor investing is, various factor models from the research, and how to do it using factor ETFs.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

Contents

What Is Factor Investing?

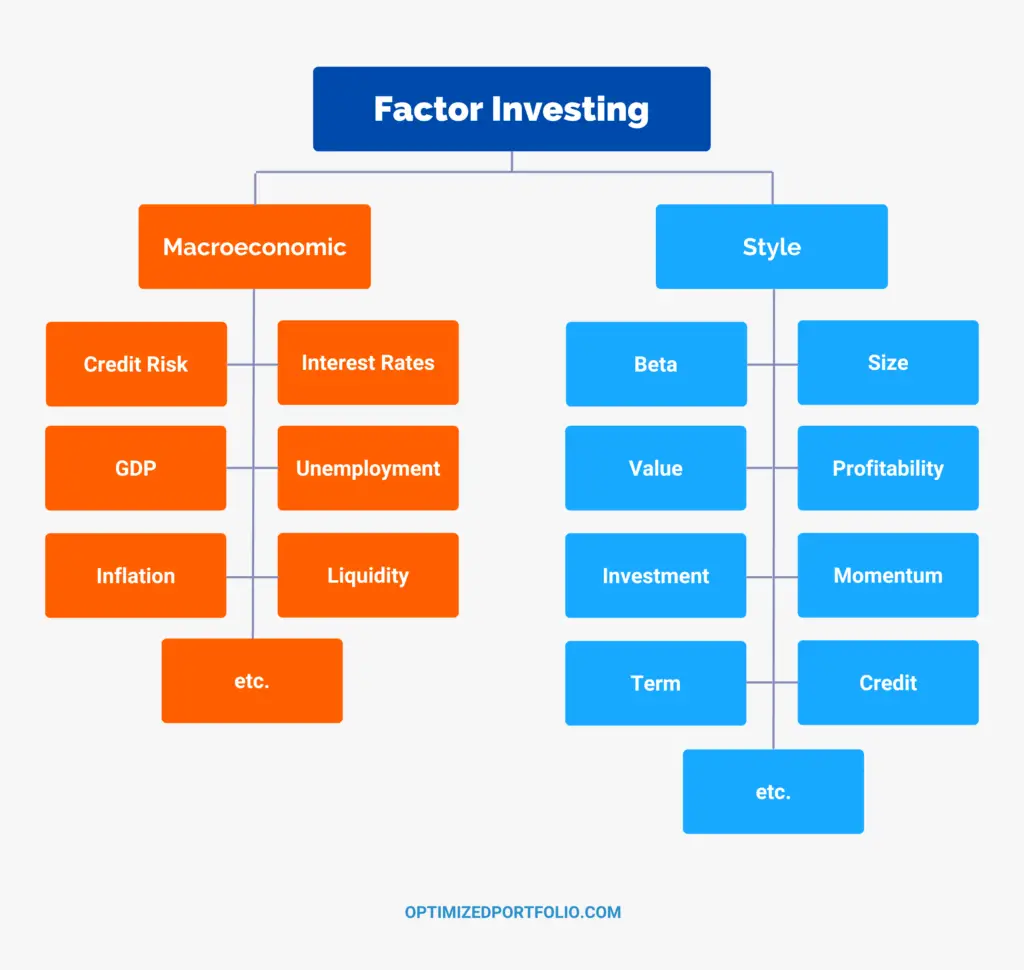

Factor investing means targeting specific drivers of portfolio returns across or within asset classes. There are two main types of factor investing: macroeconomic and style. Factor investing can simultaneously improve returns, enhance portfolio diversification, and reduce risk.

Macroeconomic factors include broad risks across asset classes like interest rates, credit risk, unemployment, GDP, inflation, and liquidity. Style factors refer to quantifiable characteristics within an asset class like Size, Value, Momentum, Profitability, Investment, Term, and Credit. Since the former are largely outside the control of the investor and since the phrase “factor investing” colloquially refers to the latter, this article will focus almost entirely on these style factors, and more specifically style factors within stocks. I'll explain their specifics later.

In that context, factor investing simply refers to consciously overweighting, or tilting, specific assets above their market weight to attempt to capture a premium (excess return) from an independent source of risk, known as a risk factor. These risk factors simply describe characteristics of assets, and explain the differences in returns between diversified portfolios previously attributed to “skill.” The handful of widely accepted factors includes Beta, Size, Value, Momentum, Profitability, and Investment. We'll explore these more later.

Factor investing involves identifying stocks and/or funds with excess exposure to these factors that can be bought wherein associated fees and transaction costs do not outweigh the expected factor premium. Note that this identification is based on observable data, not opinion or speculation. As we'll discuss below, benefits from factor investing include the obvious greater expected returns but also, conveniently and perhaps counterintuitively, lower portfolio risk by diversifying the specific sources of that risk.

There currently exist several proposed factor models, as well as criteria for including any given factor in those models.

Factor Models and Criteria

Markets, while perhaps not perfectly efficient, are sufficiently efficient to not allow for consistent, long-term exploitation. The empirical failure of active management compared to passive management is evidence of this. Index funds “work” precisely because of this reasonable market efficiency.

Since the introduction of the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), we know the market price should reflect the value of an asset based on all available information. So now the research tends to focus on asset pricing – identifying those sources of expected return within efficient markets in the form of independent risk factors outside of market beta. The models that come to mind are those like the Fama French 3 Factor Model. These models are simply attempting to identify which risk factors are empirically relevant to the pricing of assets.

A common saying in statistics is “All models are wrong; some are useful.” What this means is that models by definition are neither perfect nor 100% proven. In that sense, at some point we are choosing to “believe,” hopefully given robust evidence, that a particular model is reasonably correct enough to dictate – or at least influence – portfolio construction.

Thankfully, loads of evidence heretofore has established the pervasiveness and robustness of the handful of factors we’ll be discussing, and these factors explain about 95% of the differences in returns between diversified portfolios. Any unexplained percentage is necessarily due to luck, skill (unlikely), or, more likely, some not-yet-identified risk factor.

Researchers have claimed to identify hundreds of factors, but only a small handful have withstood the test of time and stand up to the theoretical and empirical evidence, and most usually simply end up being a subset or corollary of the established factors.

Another concern is that published models of factors will lead to their being “cursed by popularity” to the point of no longer paying a premium (or at least a lower degree of premium), which tends to happen in other areas of financial research where price differences are arbitraged away. Larry Swedroe maintains that a factor must meet 5 criteria for the premium to be expected to continue:

- Persistent – the factor holds across long time periods and different economic regimes.

- Pervasive – the factor must exist across geographies and sectors.

- Robust – the factor holds for multiple definitions (e.g., there is a value premium whether it is measured by price-to-book, earnings, cash flow, or sales).

- Investable – the factor holds after real-world implementation with fees, not just theoretically.

- Intuitive – there are logical risk- or behavior-based reasons we would expect the factor to exist.

Most of the established, accepted risk factor premiums seem to be just that – rational compensation for additional risk. So we wouldn't expect them to disappear post-publication like a factor premium with more of a behavioral basis might. That said, Cliff Asness of AQR and Wes Gray of Alpha Architect have been investigating these ideas of including behavioral explanations for the persistence of some of the factor premia.

Basically, academia is just now coming around to allowing behavioral finance into the numbers, and the research seems to indicate that factor premia may have more of a behavioral basis than was originally though. There’s a lot of noise, there’s no clear consensus, and we should probably expect a multitude of risk- and behavior-based reasons for investor preferences that contribute to the factor premia, which have evolved over time. Investors being irrational does not mean markets aren’t reasonably efficient.

If cheap stocks as a whole are riskier than expensive stocks (the basis of the Value factor), we should reliably, rationally expect to be paid a higher premium for owning them. Though note that doesn't mean cheap stocks will always outperform expensive stocks year after year; variability of returns is part of that greater risk. We just expect to be paid that risk premium on average, while accepting that periods when that bet loses may be painful and enduring. More on that later.

Swedroe concludes, based on the research, that the publication effect may diminish the degree of future premiums by about 1/3, but they shouldn't disappear: “No one expects the market-beta premium to disappear even though it has been well-known for decades. However, investors should not automatically assume that future premiums will be as large as the historical record.”

Wes Gray of Alpha Architect succinctly stated that “even though everyone knows about factors and any idiot can go do a Momentum strategy or Value strategy on their own, they're always going to work if you believe in fear and greed and you believe it's costly to arbitrage idiots.” In other words, thanks to limits to arbitrage and the unchanging nature of human behavior (i.e. biases), we would expect factor premia to persist post-publication, regardless of whether it is risk-based or behavior-based.

Now let's look at the history of factor investing and some specific factor models that came along the way.

CAPM – Capital Asset Pricing Model

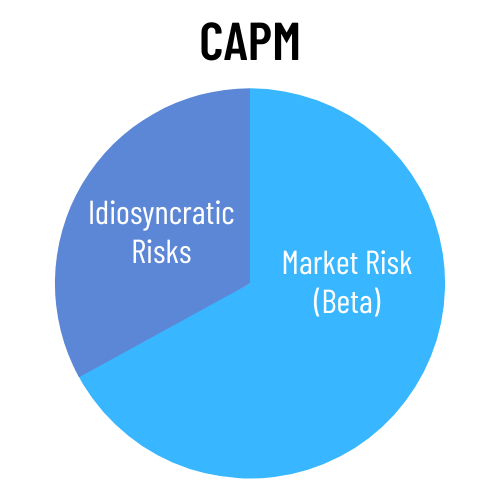

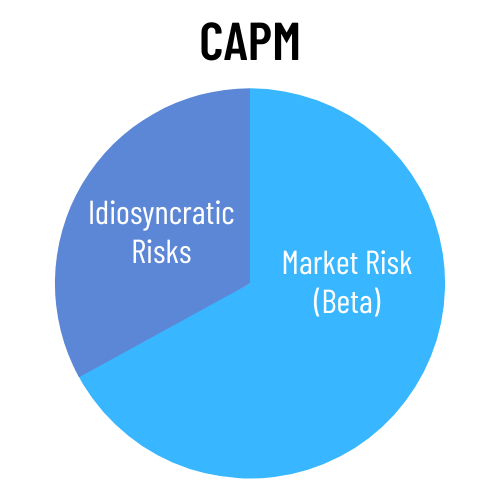

If you buy a total U.S. stock market index fund that is market cap weighted like VTI from Vanguard, for example, you have exposure to one of these risk factors – market risk, also known as market beta, the expected premium from which is called the equity premium.

Specifically, if your portfolio is 100% VTI, you have a market beta of 1. This single source of risk is your single source of expected return. I don’t mean to make that sound like a bad thing; you’re invested in the stock market for a reason – to grow your wealth via the returns from holding those stocks.

In this case, those returns are coming from your exposure to market beta. The Capital Asset Pricing Model, or CAPM, was proposed by William Sharpe, Jack Treynor, John Lintner and Jan Mossin in the 1960s. You may recognize a couple of those names as measurements of risk-adjusted return.

The CAPM, revolutionary in its time, suggested that every stock has a level of sensitivity to the movement of the broader market, its beta, which drives most of its behavior, and that any performance beyond that sensitivity is due to idiosyncratic things like new product launches, CEO changes, earnings misses, etc. The CAPM is thus the origination of factor investing and provided the foundation for Modern Portfolio Theory.

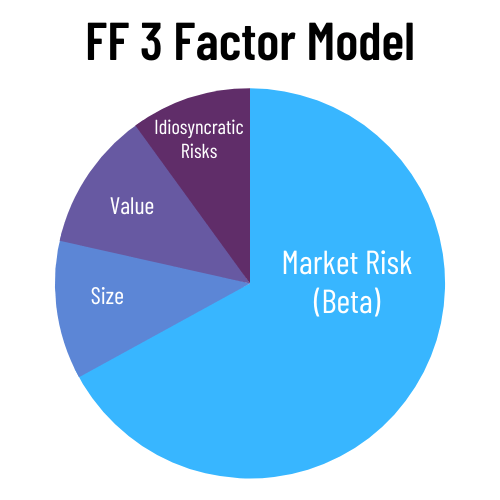

Unfortunately, market beta only explained about 2/3 of the differences in returns between diversified portfolios. Still, it is by far the largest and most important equity risk factor, so we shouldn't discard the importance of the CAPM.

Fama French 3 Factor Model

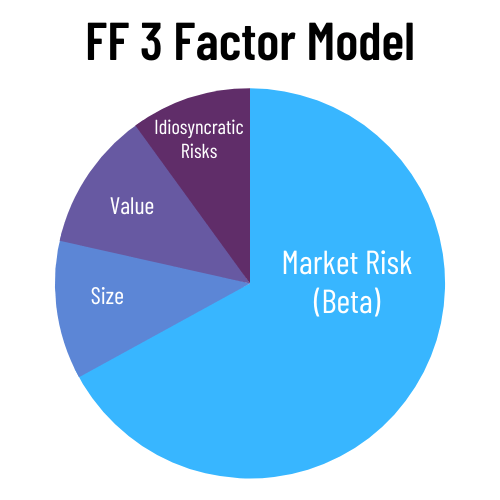

Alphas – unexplained excess risk-adjusted returns relative to the market's return – generated by actively managed funds were attributed to the “skill” of portfolio managers, and excess returns from small stocks (Rolf Banz, 1981) and Value stocks (Basu, 1977, and Rosenberg, Reid, & Lanstein, 1985) were seen as anomalous indications that markets were inefficient and were clearly mispricing these assets. For example, historically, given two diversified portfolios with the same exposure to market beta, one with excess exposure to the Value and Size factors (outsized positions in Value stocks and small-cap stocks) would have outperformed the other one.

American economists, professors, and Nobel laureates Eugene Fama and Kenneth French deduced that it was more likely that there were more independent risk factors than was the case that markets were inefficient enough for these anomalies to persist. Enter the Fama French 3 Factor Model in the early 1990's, which identified small stocks and Value stocks as additional, independent sources of risk.

Small stocks are inherently riskier than large stocks due to their greater volatility, probability of bankruptcy, and cost of capital. In theory, one need only invest in stocks with smaller market capitalizations to capture the Size factor.

Value stocks – stocks with low prices relative to their fundamental book values – are thought to be riskier than Growth stocks and tend to have more room for price movement. Investors also typically overpay for high-growth stocks about which they are overly optimistic, which may explain a lot of the Value premium. A common valuation measure is the popular price-to-earnings ratio, or P/E ratio for short.

Overweighting these types of stocks relative to their market weights has paid a premium historically, compensating investors for taking on more risk. Specifically, the Size premium refers to the returns of small stocks minus the returns of large stocks, known as small minus big or SmB. Similarly, the Value factor is high book value stocks minus low book value stocks, written as high minus low or HmL.

These two factors form the popular “style box” popularized by Morningstar, a visualization of the relative size and value of a given stock or fund, and are the framework for the modern categorization of equity securities (small/mid/large and value/growth).

The Fama French 3 Factor Model boosted the explanatory power from about 67% for the single-factor CAPM to roughly 90%, but there were still more sources of risk to be identified.

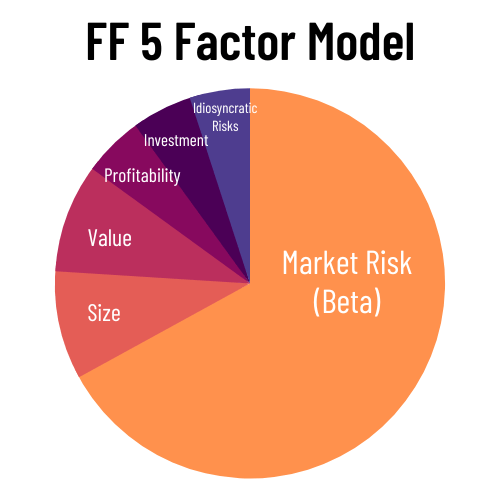

Fama French 5 Factor Model

Following the establishment of the 3 Factor Model, anomalies were still being seen: companies with conservative investment and strong profitability tended to deliver consistent alpha.

Enter the Fama French 5 Factor Model in 2015, now including Investment and Profitability (Robert Novy-Marx, 2012) as two additional independent risk factors, providing about 95% of explanatory power of the differences in returns between diversified portfolios, and intrinsically incorporating the dividend discount model. Statistical evidence for these two additional factors is weaker than the preceding three, but still reliable and robust.

The Investment factor premium describes the returns of companies with conservative investment minus the returns of companies with aggressive investment, written as conservative minus aggressive or CmA.

The Profitability factor premium describes the returns of companies with robust profitability minus the returns of companies with weak profitability, written as robust minus weak or RmW.

Carhart 4 Factor Model and the Momentum Factor

Let's back up a bit to cover Momentum. A few years after the Fama French 3 Factor Model emerged, Mark Carhart introduced a 4 Factor Model in 1997 with the addition of a factor called Momentum, based on the seminal work of Jegadeesh and Titman on cross-sectional momentum in 1993. The Momentum factor is written as MoM for monthly momentum.

The simple idea is that stocks that have been going up recently tend to keep going up for a short time, and stocks that have been going down recently tend to keep going down for a short period. A stock is considered to have positive momentum if its prior 12-month average of returns is positive.

Unfortunately, there are a few problems with the Momentum factor for long-term, buy-and-hold index investors.

First, chasing the Momentum factor invariably involves short-term market timing, either by the retail investor or, in the case of a momentum fund, the fund manager. Index investors by definition avoid – or should avoid – market timing, particularly over the short term, i.e. less than 12 months. This necessary short-term trading increases turnover from short-term buying and selling, adding greater tax liability and transaction costs, meaning it loses some points on the aforementioned “investable” criterion.

Secondly, the Momentum factor is constantly inversely correlated with the Value factor, as a Value stock by definition has just left a positive momentum phase. Thus, those investors betting on Value are inherently betting against Momentum, and vice versa. There is more robust evidence for the Value factor; I personally choose to tilt Value.

Implementation of a Momentum factor tilt is another major issue. Essentially, the Momentum factor is hard to capture and profit from in the real world after fees and the aforementioned trading costs and high turnover necessary to chase Momentum. Basically, the premium can be simulated in the lab, but can't be captured – at least so far – in a live fund in a cost-efficient way that delivers excess return to the investor.

Lastly, recall the “intuitive” criterion that factors must have a logical explanation. There's no logical explanation for the Momentum factor. Momentum appears to be behavioral in nature due to herding based on news like earnings announcements, whereas we believe Size and Value are more risk-based.

So should we simply ignore Momentum? Probably not. Both Dimensional and Avantis consider Momentum at the time of their trades to make sure they’re not betting against the factor. I’m satisfied with my exposure to it through that process.

Separate from the factor premium (cross-sectional momentum), day traders use an individual stock's momentum per se as a technical indicator (time series momentum) in a momentum-based trading strategy.

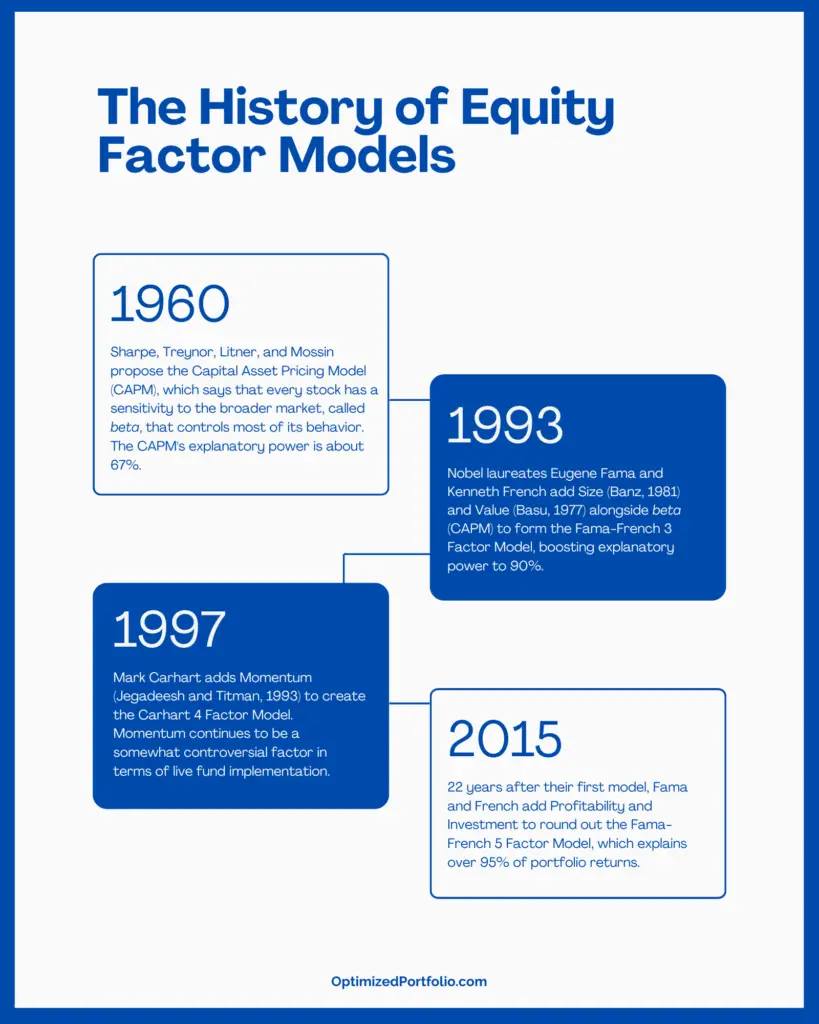

Factor Models History Infographic

To recap that history of equity factor models, here's an infographic:

Factors, Alpha, Manager “Skill,” and Dividend Irrelevance

These factor premia have been pervasive and statistically significant across geographies. Accounting for these known, systematic factors in hindsight now explains away previously seemingly inexplicable alpha generated by active managers like Warren Buffett and others who have seen any meaningful degree of long-term market outperformance.

That is, their excess returns were the direct result of excess exposure to these known factors, rendering their supposed “skill” statistically insignificant. We now know that these supposedly “skilled” active managers that were able to outperform the market were simply taking on more exposure to systematic risk, either knowingly or unknowingly.

This is not meant to take away from the efforts and success of active managers like Warren Buffett and Benjamin Graham who were able to beat the market. Basically, they were intuitively buying factors like Value and Quality before the academics “discovered” them.

Needless to say, active managers haven't been amused by the research. The identification of factor premiums puts increasingly more power in the hands of DIY retail investors – especially in the context of low-fee ETFs – who no longer need to rely on expensive fund managers for greater expected returns and risk management.

Vanguard themselves found the same thing for their own dividend funds VIG and VYM. We know that dividends per se are irrelevant, but dividend growth investors still like to claim there’s some magical alpha from dividend growth stocks. We now know the historical outperformance of collections like the Dividend Aristocrats was simply due to their excess exposure to Value, Profitability, and Investment. Intuitively, this should make sense; companies that can afford to grow their dividend consecutively each year likely invest conservatively and have strong profitability metrics. In short, while a firm's investment policy may influence expected returns, dividend policy does not influence the valuation of shares.

More importantly, not all dividend stocks have consistent exposure to these factors, and not all stocks with exposure to these factors pay dividends, making dividend stocks a suboptimal proxy for accessing the factor premia. Also note that most dividend funds have a negative Size premium (they’re mostly large caps), so you're probably better off targeting the factors directly.

Interestingly, Fama and French actually used Miller's and Modigliani's mathematical illustrations of dividend policy irrelevance to the valuation of shares (from their 1961 paper) in their construction of the 5 Factor Model. We know this “worked” because we don't observe unexplained alphas when applying the 5 Factor Model to dividend portfolios.

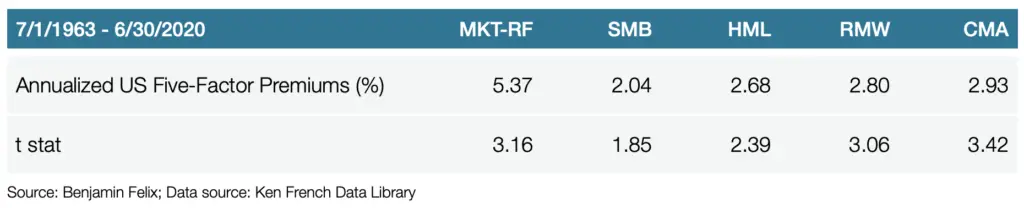

Historical Factor Premiums

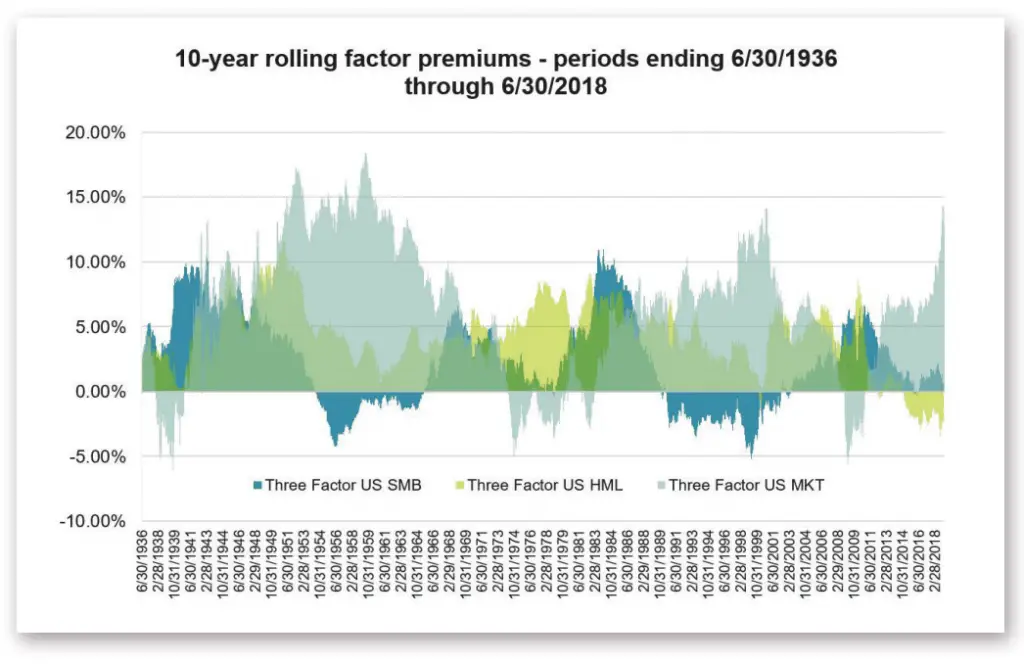

So what kind of premiums are we talking about with factors? Remember, we're simply overweighting areas of the market with greater expected returns that have been identified as drivers of portfolio performance, i.e. “factors.” The positive premiums delivered by these factors have been significant historically. Here are the historical factor premiums for the U.S. from 1963 to 2020:

Remember though that there have also been extended periods where individual factors delivered a negative premium from time to time. For example, the Value premium has suffered in recent years as large cap Growth stocks have dominated the market from roughly 2010 to 2020. But then Value beat Growth in 2021 and 2022. Fingers crossed.

But this is precisely the unexpected outcome. That is, we expect Value to beat Growth on average, but if we have a period like the last decade where the unexpected happens, it would be silly to then place a bet that the unexpected will happen again, i.e. chasing performance by flocking to large cap growth stocks and specifically Big Tech (recency bias), as many have done in recent years.

In the words of Ken French, the realized return is the expected return plus the unexpected return, and “the unexpected return can totally dominate the expected return, almost your complete performance, over any reasonable short-run period.” Short-term dominance of the unexpected outcome does not change the long-term expected outcome.

Speaking of outcomes, there's a neat asymmetry of them that favors Value stocks, which David Dreman and Michael Berry documented in a 1995 paper. They showed that when the earnings of Growth stocks are greater than expected, those stocks tended to increase in price only a little, but when those earnings were below expectations, those stocks fell by a lot. Value stocks exhibited the opposite behavior. When their earnings exceeded expectations, their share price grew drastically, and when earnings were lower than expected, share price fell only slightly.

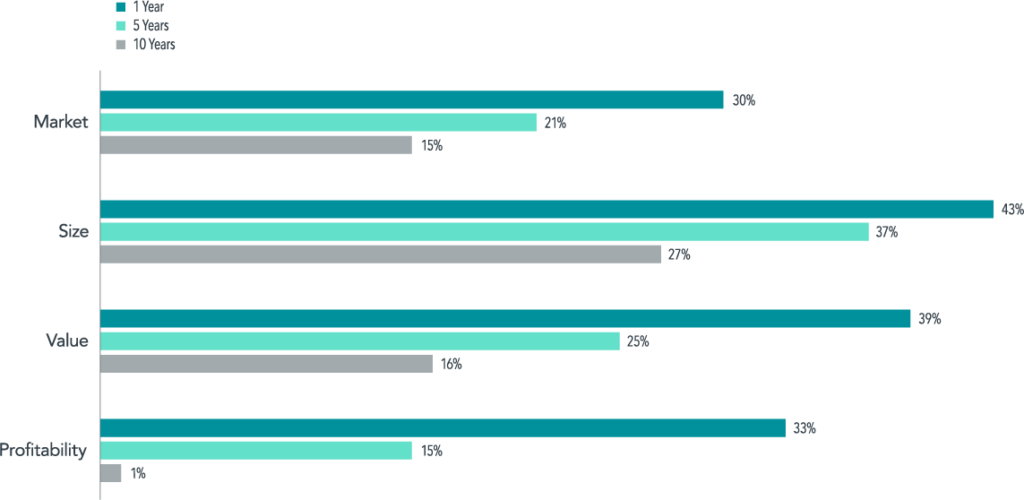

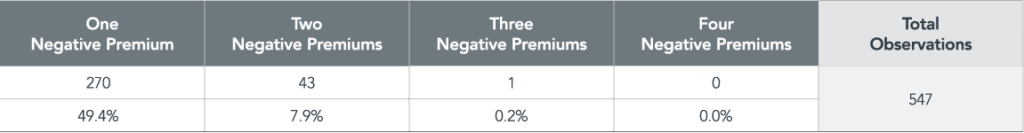

In a recent paper, Dimensional Fund Advisors showed the frequency of experiencing a negative premium in the U.S. over rolling 1-, 5-, and 10-year periods as far back as the data are available:

They stated: “As you can see, negative premiums occur from time to time. While the odds of realizing a positive premium are never guaranteed, they are decidedly in your favor and increase the longer you stay invested.”

The researchers then looked at integrating all four premiums to see how often at least one, two, three, or all of them had a negative premium over rolling 10 year periods in U.S. equities from 1963 through 2018, showing that the factors usually don't move with each other:

There were virtually zero periods where three or four factors together had negative premiums.

Keep in mind a negative premium does not necessarily mean a negative return for your portfolio. A negative Value premium simply means Growth outperformed Value, a negative Size premium simply means large stocks outperformed small stocks, and so on.

But there have also been periods of market underperformance where factors had a positive premium. Value stocks have actually delivered a more reliable premium than the market historically. This is illustrated below.

I don’t employ or advise market timing, but AQR maintains that Value is basically the cheapest it’s ever been right now relative to history with the largest valuation spread between Value and Growth (meaning Value is looking cheap and Growth is looking expensive), suggesting that now may actually be the worst time to give up on the factor, and that it’s due for a comeback. Value beat Growth in 2021 and 2022, so that comeback may be happening.

The historical data supports this suggestion of a significant, positive expected premium for so-called “deep value.” In March, 2021, Yara, Boonz, and Tamoni concluded that large value spreads have reliably preceded greater returns for Value and have provided statistically significant predictive power for those attempting to time Value, i.e. rotating in and out of Value stocks. Moreover, there has existed a positive relationship between the size of the spread and the future premium delivered – that is, the larger the spread, the larger the expected premium.

Dimensional also looked at next 10-year periods following a 10-year period where a factor had a negative premium, and noted “that premiums have, on average, been positive after periods of underperformance, although the data show a wide range of outcomes.”

Larry Swedroe notes: “If you are not convinced you have that strong belief system, a necessary condition for having the discipline and patience you will need to maintain your exposure to a factor through those inevitable bad times, you should not invest in that factor, and that includes market beta.”

As usual, stick to your strategy and stay the course.

Interestingly, the later three factors besides Size in the 5-Factor Model all seem to deliver greater statistically significant alphas within small-cap stocks. That is, if you can identify small-caps that exhibit Value, conservative investment, and strong future profitability, those independent risk factors will deliver greater returns than the same exposure in large-caps. That said, I wouldn’t sacrifice the cap size diversification to solely chase factors within small caps.

Some argue that small stocks are just higher beta stocks and that there’s no actual Size factor. I say that’s semantics and I don’t really care what we call it; if we expect the equity premium to be positive over the long term, then we expect higher beta stocks to outperform the market over the long term.

We also probably shouldn’t be surprised to see the Size premium suffering during a period of extremely low interest rates that provides easy, seemingly endless capital for mega caps with global reach. This doesn’t mean you should try to time the Size premium (or any factor premium, for that matter), because interest rate changes are unpredictable.

The Size premium does not seem to apply to small cap growth stocks. Swedroe calls them a “black hole” in investing. Removing them from the data set improves the historical returns of the Size premium significantly. AQR submits that the Size premium is only “resurrected” if you “control your junk” by removing those pesky, wild small cap growth stocks with weak profitability. Thus, it’s probably a good idea to only focus on small cap value.

Diversification Benefit From Factor Investing

So at this point, we know that additional expected returns are a major reason to overweight certain factors in your portfolio, but there’s another bonus that is arguably more important. Most seasoned investors know it’s sensible to diversify across things like asset types, geographies, cap sizes, equity styles, and sectors. But what is perhaps less obvious is that it also makes sense to diversify across the aforementioned systematic, independent sources of risk within stocks, known colloquially as factors.

A traditional 60/40 portfolio using intermediate bonds still has over 90% exposure to one type of risk: market beta. This concept also shows up in high-yield corporate bonds, which, despite the name, have a significant amount of equity risk exposure. Viewing the portfolio through a factor lens allows for more efficient capital allocation.

Conveniently, the factors are all lowly correlated to each other and in some cases are negatively correlated, as is usually the case with Value and Momentum. That is, their risk premia show up at different times relative to each other (and perhaps most importantly, relative to market beta), giving you a statistically better chance of weathering market turmoil better with lower volatility and risk over the long term (narrower distribution of outcomes = greater precision and reliability) compared to a market cap weighted portfolio relying solely on market beta. What is more astounding is that these correlations between factors are usually lower than the correlations between stocks in different geographies and in some cases even lower than the correlations between stocks and bonds.

Specifically, Louis Scott and Stefano Cavaglia looked at the Beta, Size, Value, Quality, and Momentum factor premia, and observed that:

- Size tends to move with the market, as we'd probably expect.

- Quality and Momentum are countercyclical to the market.

- Value appeared to be countercyclical but was statistically weak.

This theoretical and empirical diversification benefit may seem counterintuitive at first, as we know factor tilts increase expected returns by taking on greater systematic risk. But by diversifying the independent sources of that risk, the portfolio as a whole becomes less risky when we add them all up. Scott and Cavaglia found that the distribution of outcomes (think sequence risk and specifically, tail risk) was improved by overweighting any one of the factors, and was improved comparatively more when equal-weighted tilts of all the factors were added.

Here's the kicker. They then investigated if this diversification benefit would remain if the factor premia were lower, which we might expect for the future due to the publication effect. They cut all the premiums by 50% and found that the diversification benefit did indeed remain intact. This has important behavioral implications as well, as it shows that for the factor investor who tilts toward one factor can minimize tracking error regret – the regret felt after underperforming a popular index like the S&P 500 – by diversifying across additional factors.

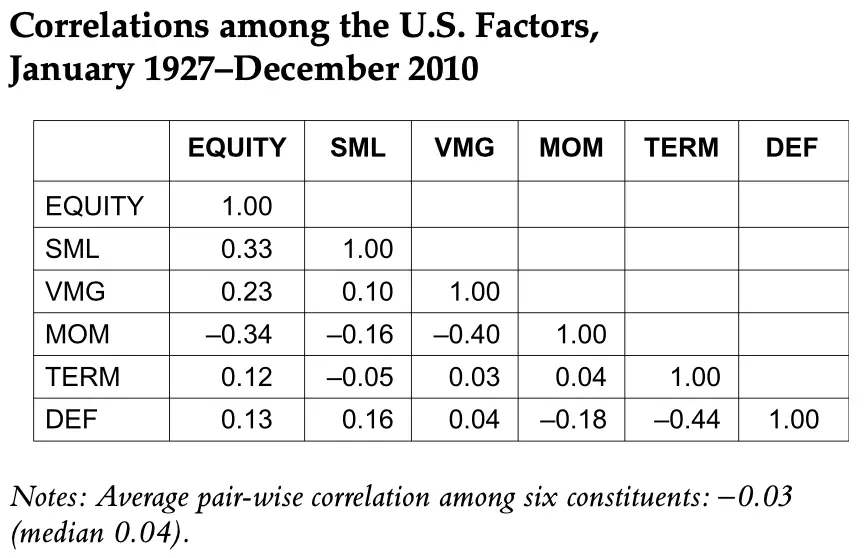

Antti Ilmanen and Jared Kizer performed similar analyses and even concluded, after observing the factor correlations, that factor diversification “has been much more effective in reducing portfolio volatility and market directionality than asset class diversification,” which is pretty staggering. Here are those correlations below between factors in the U.S. The chart uses “EQUITY” for market beta, “SML” for Size, and “VMG” for Value. It also includes the fixed income risk factors term (“TERM”) and default/credit (“DEF”):

They concluded:

The argument that we make for factor diversification partly rests on the expectation that the positive factor premia will continue to persist. But the correlations (or relative lack thereof) of these premia with each other are at least as important. … Factor diversification is highly effective because the average correlation between the five constituents is virtually zero. … It is hard not to conclude that smart investors should include cost-effectively sourced dynamic factor premia into long-term portfolio allocations.

Granted, Ilmanen and Kizer were using long-short portfolios in their research to maximize factor exposure, but they maintain that the results and their implications are still very significant for long-only portfolios. They also noted that they obviously don't expect investors to jump from asset class diversification to factor diversification, and that the more sensible, more realistic approach is likely to employ “traditional” asset class diversification and then also overlay factor diversification.

Once again, diversification appears to be the only free lunch, this time in a slightly more nuanced way that conveniently should deliver higher expected returns and almost certainly higher risk-adjusted returns. This conveniently makes factor tilts appropriate for young investors and retirees alike, across all risk tolerances. Just remember the inherent short-term cyclicality of factors, which may introduce tracking error regret.

Even if you don't believe that the premia (i.e. greater expected returns) will persist, there's a compelling case to add factor tilts for the separate diversification benefit alone. Scott and Cavaglia summarized this as follows:

Our result which favors a portfolio of factor premia overlay remains unchanged. As previously suggested, the benefit of factor premia is not in their mean returns, but rather in their ability to mitigate adverse conditions…

How To Invest in Factors Using Factor ETFs (Factor-Based Funds)

So now that we know some important reasons why we may want to tilt, or overweight, certain factors, let’s look at the practical implications in terms factor ETFs or “factor-based funds.”

Identifying factors is one thing. The effective implementation of factor tilts in a real-world portfolio in a cost-efficient manner is another altogether. This is a key distinction, as academia (the people doing the identifying) doesn't consider and doesn't care about things like fees, turnover, transaction costs, and liquidity. The original studies on factors weren't concerned with whether those factors were actually investable, and the hypothetical factor portfolios used were not designed for actual implementation.

Since the discovery and acceptance of some of these factors has been relatively new, we’re just now seeing financial products (i.e. ETFs) emerge to target them that are available to the public. The unfortunate reality, however, is most of these products are simply using terms like “factor” and “smart beta” as marketing buzzwords, and the actual factor loading of these funds varies wildly. Ironically, funds with “factor” in their name tend to deliver poorer factor exposure than those without it that have existed for years. Ben Felix, portfolio manager at PWL Capital, notes:

“There are low-cost ETF products that have existed for many years which are better positioned to deliver on factor premiums than most so-called factor funds. A fund that is called a factor fund seems to automatically command a higher fee despite not being positioned to deliver on factor returns.”

For example, two different funds claiming to be “Value factor” funds may have very different loading (exposure) on the actual Value factor as determined by the Fama-French models, so don’t just go buying any fund with “factor” in the name. A regression analysis is used to explore a fund’s true factor exposure.

Fees can be another issue. Newer “factor” funds are almost always more expensive than “normal” index ETFs. Even factor-based funds that are able to reliably provide factor exposure may not be able to deliver a positive expected premium after those fees and transaction costs are accounted for, such as in the case of Momentum. Thankfully, costs have decreased dramatically in just the past year or two on these types of products as retail investors demand lower fees. Previously, costs were usually prohibitive for tilts like these, offsetting any expected excess returns.

Inefficient, generic factor products can also result in unnecessarily higher turnover and unwanted sector or industry concentrations. Efficient factor strategies, on the other hand, are designed to ensure that providing positive exposure to one factor does not automatically mean negative exposure to others, and will aim to mitigate turnover and trading costs. Factors investors must pay close attention to what they're buying and choose providers wisely.

Dimensional Fund Advisors (DFA) is probably the gold standard in this space of factor tilts in terms of investable financial products, but previously retail investors couldn't buy them. DFA recently launched a few broad ETFs with light factor tilts that may be a good option for an investor wanting a simple solution that mimics a market index fund but overlays factor targeting for Size, Value, and Profitability. They've also been converting their mutual funds to ETFs, making them much more accessible to retail investors.

A few former employees of DFA left and started Avantis, which has some good ETF options for more granular factor targeting like AVUV for U.S. small cap value, for example, at a cost of only 25 basis points. Conveniently, earnings screens in small value funds like VIOV incidentally (and in the case of AVUV, purposefully) get you some exposure to the Investment and Profitability factors as well. I hold AVUV in my own portfolio.

To my knowledge, there are still no good, affordable funds available that specifically target the Investment and Profitability factors per se, except through multi-factor funds and $QUAL from iShares which targets Quality, a separate factor that is highly correlated with and largely interchangeable with Profitability. But as shown above, it's probably best to get exposure to multiple factors anyway instead of singling one out. Conveniently, $AVUV from Avantis provides greater exposure to the Profitability factor than $QUAL.

Some popular lazy portfolios that employ factor tilts are:

- Ben Felix Factor Portfolio

- Paul Merriman Ultimate Buy & Hold Portfolio

- Paul Merriman 4 Fund Portfolio

- Larry Swedroe Portfolio

- Tim Maurer Simple Money Portfolio

- Golden Butterfly Portfolio

- Vigorous Value Portfolio

- Factor Tank Portfolio

We also have to take a second to acknowledge that factor investing is somewhat in between the extremes of passive indexing via a cap weighted index fund and active, speculative stock selection. In that sense, it's been said that factor investing is a third type of investing. Moreover, it's important to recognize that factor investing is not designed to fully replace either of those two extremes.

In fairness, the factor-based funds I'm usually advocating for, such as those from Avantis or DFA, are transparent, low-cost, and rules-based, meaning managers are objectively screening for stocks using strict parameters and observable data rather than simply by opaque, expensive strategies based on opinions or feelings, which is what we usually mean when we say “active.”

I'm the first to admit that active versus passive is a sliding scale and not a binary on/off switch, but recognize that a factor-tilted portfolio's composition and behavior will not look like that of the market, for better or for worse. As such, factor investing is arguably only appropriate for the experienced investor who truly understands what they're doing and who can stay the course during potential periods of market underperformance. A multi-factor approach will minimize that underperformance (and subsequent tracking error regret) over the short-term because it diversifies the inherent cyclicality of the different factors.

Conclusion

Factor investing involves targeting independent sources of risk for the sake of diversification and greater expected returns. There are only a handful of factors that stand up to the theoretical data and out-of-sample empirical evidence. Several factor models exist based on these, providing upwards of 90% explanatory power of the differences in returns between diversified portfolios, thereby virtually eliminating the idea that some active managers deliver alpha due to their “skill.”

Implementation is the crucial piece of the factor investing puzzle. Pay attention to a fund's characteristics and factor loading. The majority of “factor” ETFs out there are simply using the term as marketing and provide poor factor exposure at higher fees. Ironically, investors are likely better off going with low-cost funds that have been around for years, at least for Size and Value, as sufficient proxies for factor exposure, such as $IUSV from iShares and $VIOV from Vanguard.

Recall that I mentioned having to “believe” in a model in some sense. Understandably, this can be a hurdle for investors in adopting factor investing. At first glance, factors almost seem like magic, especially with the claim of greater expected returns and lower portfolio risk. I'm a skeptic and a pragmatist by nature. I'll admit that it took a lot of research and reading for me to adopt factors. One of the simple yet profound realizations for me was that if you invest in the stock market at all, you are intrinsically choosing to “believe” in the market beta factor, so you must necessarily also, by definition, at least to some meaningful degree, “believe” in other risk factors like Size and Value. If we have additional reliable pieces of information in terms of variables other than market beta, why wouldn't we want to make use of them? Specifically, if we can identify expected premiums outside of the equity premium, why wouldn't we want to also invest in those?

Do you employ factor tilts in your portfolio? Let me know in the comments.

Disclosures: I am long AVUV in my own portfolio.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Hi, I enjoyed your article which made a compelling case for factor investing. What are your thoughts on 2 belowmentioned sources: 1) Rick Ferri on Boglehead university ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e7_MFyltNt4 ) and 2) a recent episode of Rational Reminder where Andrew Chen did not find evidence of excess returns in his research ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLbz3vKdZxM ) ?

Great article! very informative, Went down a long rabbit hole after reading this. Thanks!

I did a lot and lot and lot of looking into factor funds a few years ago. I tried to focus on profitabliity/quality, size and value. My first choice wasn’t available on M1 and still isnt, but it was FLQL.. Instead I went with LRGF and INTF for international.

I did like VFMF for a consolidated one too along with ACWF, but they didn’t capture all of the factors like I wanted them too.

For international, I found a few interesting ones but again, no true winners.

FNDF doesn’t really tilt but they do focus on large cap with good cash flow

RODM seems well rounded.

IQLT was my quality pick, but still not a great overall choice.

I sinked in hundreds of hours of reading the studies found on Ben’s channel, RR podcast, RR community and all the sources I found along the way (FF, AQR, AA, DFA, Merriman, here etc.), Guide to Factor Indexing, Your blog is quality stuff. I’m far from an expert, not even close to the folks making regressions on the RR community, but I have to say your blog is quality. I only wish I found it sooner.

(BTW, I’m one of those apes that’s on AVUV/AVDV/AVES, 50% US/35% DEV/15% EM, with the caveat that not my whole retirement relies on those funds. I look at my pension like the bond portion of it. I think folks on the RR community call it the No Sleep Portfolio™.)

I’m off to read your bond articles since I want to put my emergency fund to work. Do you happen to have a good reading recommendation for bonds, and perhaps something to follow-up on Guide to Factor Indexing that I just finished? Maybe a reading list would be something you’re interested in?

Thanks so much for the kind words and for the thoughtful comment! This page is somewhat of a reference guide that links out to different posts. For bonds specifically, this one is arguably the most important, talking about treasury bonds vs. corporate bonds. This post discusses the purpose of bonds. Just did a post on I Bonds, which are very relevant right now. And here’s a post specifically on investing one’s emergency fund.

Thank you for the in-depth article on factor investing. I have been considering a Paul Merriman Ultimate Buy and Hold portfolio (or variant) and your article really helped give me a better understanding of his fund selections and allocations.

One thing I have run into when researching the Merriman portfolios is a fair bit of negative comments on a few forums about his portfolios (and therefore by my own inference factor-based portfolios) not being good for investors nearing or in retirement. I’m about five years out. The negative comments typically center around the potential for long stretches of underperformance and being able to withstand them during retirement years. Therefore, factor based portfolios are better suited for younger investors. Merriman himself also seems to spend a lot of time in his podcasts focusing on younger investors.

If I’m understanding a key point in your article, a big benefit of a factor approach is decreased risk which could be a very beneficial to an investor with a shorter time horizon.

Any thoughts you may have on an older investor moving to a factor-based portfolio would be appreciated.

Hey Steve, glad you found it useful! You basically said exactly what I would say. The vast majority of “factor investors,” let’s call them, either don’t know about or seem to forget about that diversification benefit of factor tilts irrespective of the expected premiums. Moreover, I don’t try to time the market, but it would be somewhat irresponsible to ignore the fact that the current market is also extremely concentrated in large cap growth, so I would argue overweighting small cap value makes even more sense right now. In fairness, in this context of diversification being the primary goal, it may also be prudent to include Momentum as I did with the Factor Tank Portfolio, whereas Merriman doesn’t specifically include Momentum. Hope this helps!

I wonder how SCHD scores on the profitability and investment factors.

Interesting. More on profitability (.34) and investment (.21) but not much on value (.12).

Hi John, you’ve got a fantastic compilation of details on your conclusions drawn from your reading of the factor investing research! I want to just add that Larry Swedroe advocates for the use of rebalancing bands to provide natural exposure to the momentum factor. I think it’s worth a mention. Specifically, he states :

“If [you] use rebalancing bands as I recommend with the 5/25 rule you already incorporate MOM into portfolios, and buy and hold ranges which all the funds I recommend/use also incorporate momentum.”

Thanks Daniel! I’ll definitely check that out and add it to the post. Appreciate the suggestion.

Thanks for the reply John !

Have you taken a look at multi factor funds like JPUS, VFMF or LRGF ? From what I have seen, their tilts seem to be rather anemic compared to dimensional’s and avantis’ offerings.

Really wish avantis would have a one fund solution soon !

Thanks,

Matthew

You hit the nail on the head. These “multifactor” funds tend to do a pretty poor job of what they’re claiming to deliver, at least so far in their relatively short lifespans. This makes sense, as it’s hard (maybe impossible) to create a single basket of stocks in one fund with positive loading on all factors, since we know the factors are lowly correlated (and sometimes inversely correlated) to each other.

That said, I’ll say VFMF is probably the “best” I’ve seen of these funds, and is conveniently also the cheapest, so it may be a sensible choice for the investor who wants a single-fund solution.

DFA and Avantis recently released DFAU and AVUS respectively, but they’re basically market-like exposure with very light factor tilts.

Some great stuff here! I have been reading up on risk premiums and you seem to have summarized it perfectly.

My question is how do you evaluate how good a fund is at tilting towards those factors. For example, what do you think about VFVA vs say VIOV?

Also a second question is if I’m wanting to max out my risk and tilt the heaviest toward factor investing since I’m young, is the vigorous value lazy portfolio your recommendation or your 100% stock ginger ale or maybe even something else like 100% VFMF?

Thank you very much. The content on this website must have taken a lot of hard work and time to learn and then to produce.

Thanks so much for the kind words, Justin! Really glad you’ve found the content helpful!

You can use tools like Portfolio Visualizer to perform what’s called a regression analysis on a fund’s factor loading, showing you numerical values for historical exposure to each factor in a particular model of your choosing. Beyond that, we can look at valuation metrics like P/E to compare funds as well.

VFVA provides some nice exposure to Value, but VIOV does so more within small caps, so they’re two different things.

I noted in another comment here that VFMF is probably the “best” multifactor fund I’ve seen and is conveniently the cheapest, so that’d be fine for a simple one-fund solution.

I think the choice of portfolio comes down to how granular you want to get (i.e. simplicity with VFMF vs. multiple funds) and what degree of factor tilt you’re comfortable with to where you won’t have tracking error regret if we see a decade of underperformance, for example, as with Value over the past decade or so. Basically, what’s going to still allow you to sleep easy at night and stay the course? The new DFA funds also provide a simple solution for broad market exposure with light factor tilts, but it sounds like you may be interested in a larger bet.

I’m biased obviously toward something like my Ginger Ale that puts a lot of focus on the small cap value universe globally. If you want to tilt Value in large caps too like Paul Merriman does, the Vigorous Value is a fine choice as well IMHO.

In any case, if you go with multiple funds, Avantis objectively seems like the way to go for most of them at this time. I delved into the intricacies of the factor exposure for small cap value here, for example, that may give you a better understanding of how we approach evaluating these different funds and why we’d choose one over another. Merriman does the same thing each year with his “best in class ETFs” list and explains why he swaps out one fund for another when a new one becomes available, such as the case recently with these new Avantis funds; he’s a big fan of them.

Conveniently, remember too that factor diversification actually decreases portfolio risk over the long term, which is a huge benefit that may be of even larger significance than the greater expected returns.

Thank you for your long detailed and dedicated response. Such dedication is rare and you should consider making a youtube channel called optimizedportfolio. I would watch every video and I believe others will as well.

I am leaning towards either your 100% stock Ginger Ale or Vigorous Value. Since my time horizon is probably a minimum 30 years with max risk, I’m even thinking about your hedgefundie allocation.

Do you consider 100% stock Ginger Ale to be more factor tilted or Vigorous Value? As noted, you said vigrous value tilts value in large cap too while ginger ale focuses on small value.

Keep up the amazing work!

Thanks! YouTube is here! Though admittedly I’ve been slacking on the videos.

Maybe do a lazy portfolio and then throw 5-10% in the Hedgefundie Adventure as a lottery ticket.

Vigorous Value is slightly more factor tilted than Ginger Ale. Slightly higher allocation to small caps and then obviously a big bet on Value overall.

Thanks, will do! It’s comments like yours that keep me motivated to keep doing this.

A global cap weight portfolio of Avantis US (AVUS), International (AVDE) and Emerging (AVDE) has performed better than combining their SV/V funds with a cap weight global total market index fund.

While the factor slants of AVUS, AVDE, and AVEM might appear modest, these funds seem designed to provide balanced factor exposure to provide the best risk-adjusted returns.

That doesn’t mean anything. These funds have only been out about for about 2 years.

Hi Jon,

Fantastic article ! Keep up the amazing work ! I have just been thinking since value, or indeed any other factor, is a subset of market, we can expect that it is comprised of a smaller number of securities, if so how much of its returns are driven by the factor explanation, and how much could be attributed to the wider dispersion of outcomes caused by concentration ?

Thanks,

Matthew

Thanks for the kind words, Matthew! Glad you enjoyed it.

That’s actually the beauty of factor tilts that took a second to wrap my head around when I first learned it and that at first glance perhaps seems counterintuitive – by overweighting others like Size and Value, we’re moving away from the typical concentration in market beta and actually narrowing the distribution of outcomes.