Financially reviewed by Patrick Flood, CFA.

The 60/40 Portfolio has long been the go-to cornerstone for medium-risk investing for all ages. Recent speculation suggests it might be “dead.” Here we’ll investigate that proposition and take a look at the portfolio's components, historical performance, and the best ETF’s to use in its implementation.

Interested in more Lazy Portfolios? See the full list here.

Disclosure: Some of the links on this page are referral links. At no additional cost to you, if you choose to make a purchase or sign up for a service after clicking through those links, I may receive a small commission. This allows me to continue producing high-quality content on this site and pays for the occasional cup of coffee. I have first-hand experience with every product or service I recommend, and I recommend them because I genuinely believe they are useful, not because of the commission I may get. Read more here.

Contents

What is the 60/40 Portfolio?

The 60/40 Portfolio has served as a cornerstone asset allocation of long-term investing for decades, originally borne of the simple desire for one's investments to survive downtowns, something that a 100% stocks portfolio may not always do without a sufficiently long investing horizon. Peter Bernstein considered the 60/40 portfolio to be the “center of gravity” between risk and return.

As the name implies, the 60/40 Portfolio is simply a portfolio comprised of 60% stocks and 40% bonds. The premise is that the uncorrelation of bonds to stocks increases diversification, reduces volatility, and helps protect against drawdowns and black swan events.

The specific allocation has historically been a moderate balance of stock-driven returns and bond-driven risk reduction. Interestingly, the rationale behind the specific 60/40 allocation was originally largely based simply on tradition and intuition, which was later affirmed by modern portfolio theory. As an aside, there's a fund called NTSX that takes this idea and applies 1.5x leverage to it for 90/60 exposure.

The 60/40 portfolio is as follows:

- 60% Stocks

- 40% Bonds

Let's look at specific asset choices.

Stocks

For the 60% stocks position, we have several choices. You could choose to use the S&P 500 index, the total U.S. stock market, the total world stock market, the Russell 1000 index, etc. To broadly diversify across U.S. stocks, I’m suggesting the use of a total U.S. stock market fund, to get some exposure to small- and mid-cap stocks, which have outperformed large-cap stocks historically due to the Size factor premium. I'll explore a globally-diversified option below later in this post.

Bonds

For bonds, the obvious and popular choice is a total bond market fund, but since we know treasury bonds are superior to corporate bonds, I’m suggesting intermediate treasury bonds, which should roughly match the average duration of the total U.S. treasury bond market.

Long-term bonds are likely too volatile – and too susceptible to interest rate risk – for older investors, and short-term bonds are too conservative for young investors at a 40% allocation, so intermediate-term bonds offer a happy medium that is suitable for most investors.

For that reason, my blanket recommendation for a one-fund, one-size-fits-most bond choice would be intermediate-term treasury bonds, which should roughly match the average maturity of the total treasury bond market. I have to speak to the “average investor” in this post.

I also obviously acknowledge that, again, an equity-heavy portfolio will likely outperform a 60/40 portfolio over the long-term in terms of pure return. I wouldn't suggest that young investors take up a significant allocation to bonds from the start unless they consciously realize they have a low tolerance for risk and volatility. We'll explore this more below.

Recall too that Warren Buffett himself plans to put his wife's estate in a 90/10 portfolio with 10% in short-term treasury bonds, and recent research shows a historically safe withdrawal rate not far off from that of a 60/40 portfolio. I delved into that a little in this blog post about the Warren Buffet Portfolio.

Is the 60/40 Portfolio Dead? Probably Not

Pundits have been reciting for years that the “60/40 portfolio is dead,” positing that investors should embrace a higher allocation to equities going forward. I don't necessarily disagree with that idea per se, as stocks tend to outperform bonds, but I also don't think their hyperbolic opinion of the 60/40 being “dead” is accurate.

Part of their assumption is also that a young, new investor will be taking up a 60/40 asset allocation. I would argue that's likely not the case. Assuming a retirement age of 60, I use [age-20] as a general rule of thumb for bond allocation. One can obviously titrate that up or down based on personal risk tolerance.

This means a 20-year-old would be 100% equities, and a 30-year-old would have 10% allocated to bonds. Even then, they can afford to use longer-duration bonds like long-term treasuries, at least for a while, that should allow for higher returns over the long-term.

Moreover, while the somewhat reliable historical relationship between stocks and bonds may indeed be decreasing, that doesn't mean it's “dead.” Bonds still offer the lowest correlation – usually negative – to stocks of any asset.

Bond Behavior with Low, Zero, Negative, or Rising Interest Rates

At the time of writing, many people also complain of bonds' “historically low yield,” and parrot that “interest rates will begin rising” from their current “record lows,” which they say will hurt bonds. People have also been claiming that “interest rates can only go up” every year for the past decade, while they haven't. Moreover, zero and negative rates are not out of the question. I would submit that the complaintive chatter over low yield and the potential for rising rates is quite literally short-term noise.

Arguably more importantly, there's no reason to expect interest rates to rise just because they are low. They have gradually declined for the last 700 years without reversion to the mean.

I acknowledge that post-Volcker monetary policy, resulting in falling interest rates, has driven the particularly stellar returns of the bond bull market since 1982, but I also think the Fed and U.S. monetary policy are fundamentally different since the Volcker era, likely allowing us to avoid hyperinflationary environments like the late 1970's going forward.

I also concede that interest rate risk is real, but bonds are unfairly maligned. Intuitively, bonds do appear more attractive at higher interest rates, but they shouldn't be feared at low/zero/negative/rising rates. Let's explore why.

Capital Appreciation – Bonds Have Returns Too

Bond naysayers who complain of low yields and rising rates seem to forget the simple fact that bonds have returns too, and that in a long-term lazy portfolio, we're more interested in their uncorrelation to stocks and how that reduces the portfolio's overall volatility, regardless of the bond duration used, not holding bonds in isolation.

A bond is essentially just a loan that you provide and for which you receive periodic interest payments over time until the bond reaches “maturity.” A simplistic explanation of bonds' change in value is this: When market interest rates fall, capital appreciation occurs because your bond's higher coupon payment is now worth more. Conversely, when market interest rates rise, your bond's lower coupon payment is now worth less.

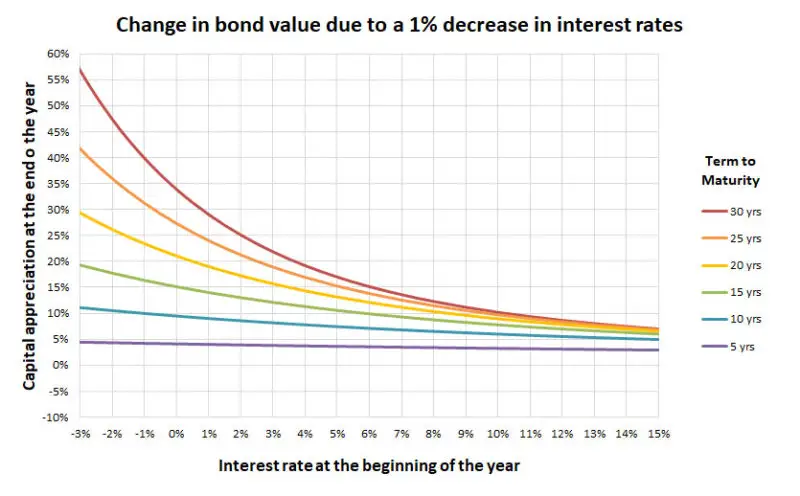

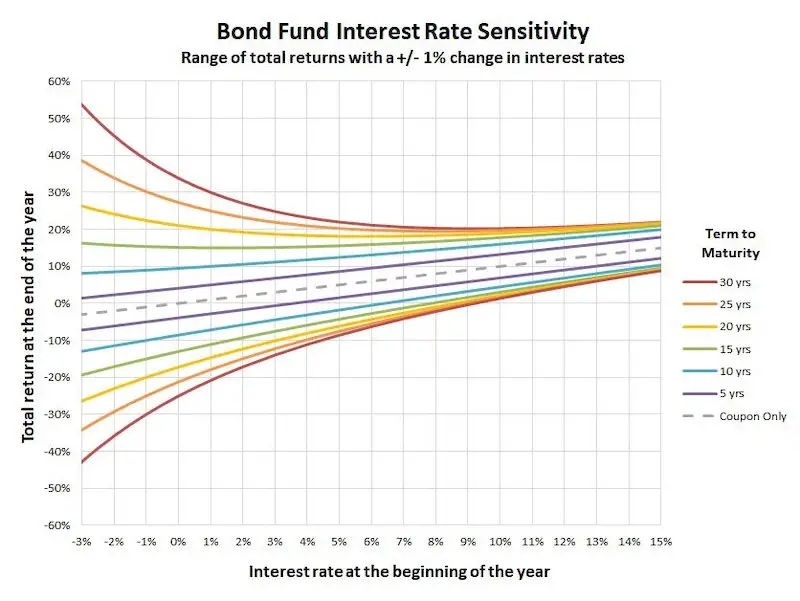

Bonds with an effective duration of 5 years, for example, are expected to change in value by 5% for every 1% change in the market interest rate. As such, long-term bonds (longer durations) are more volatile – and more affected by interest rate changes – than short-term bonds:

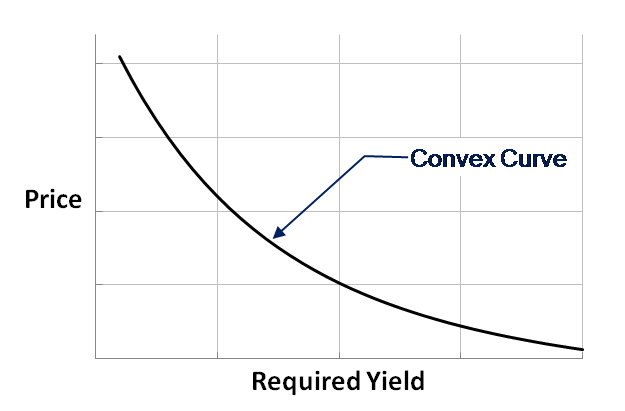

Bond Convexity

A subtle and complex yet beautiful concept illustrates why we shouldn't avoid bonds; it's called bond convexity. Tyler over at PortfolioCharts.com does a great job of explaining this concept comprehensively here for those who are interested. I'll attempt to summarize it below.

The aforementioned exemplary inverse relationship of bond price sensitivity to market interest rates is not one of linearity. That relationship is actually a curve. The shape of this curve is referred to as convexity. The effect of this convexity is greater as bond maturity increases:

The above image is simply an illustration of the effect of bond duration and interest rate changes on bonds' capital appreciation. As you can see, even in a negative rate environment, a 1% drop in interest rate results in significant gains for a 30-year bond, while the incremental gains for 5-year bonds are relatively flat.

Incorporating coupon payments, lower-interest-rate long-term bonds experience greater gains than high-interest-rate long-term bonds.

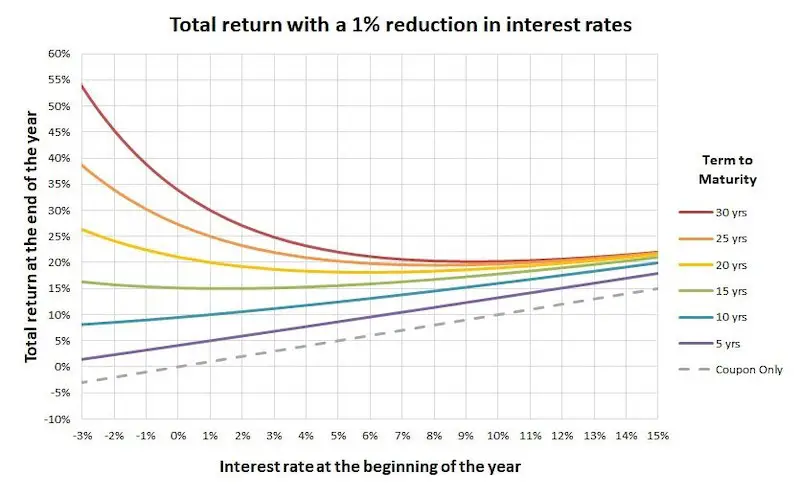

Now let's look at the potential downside with rising rates:

As we would expect, a bond's interest payment becomes more important at higher interest rates, and capital appreciation becomes more important at low interest rates.

The important takeaway is that bond risk and returns are asymmetrical, and that asymmetry favors the upside.

This again supports our use of intermediate-term bonds: long-term bonds capture significant returns when interest rates decline, while short-term bonds are safe in a rising rate environment.

60/40 Portfolio Historical Performance

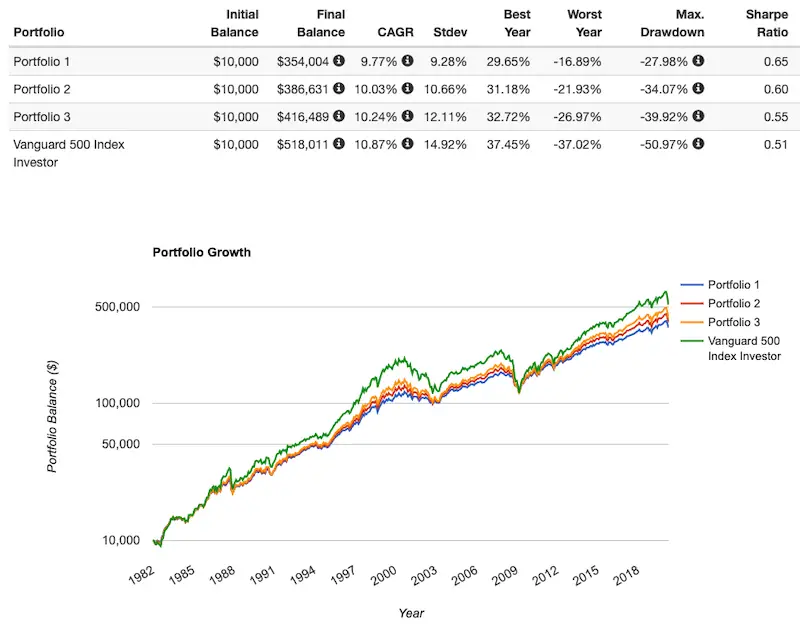

I decided to run a backtest to look at the historical performance of the 60/40 portfolio against a 70/30, 80/20, and the S&P 500 index. Based on my comments about U.S. monetary policy, I started the backtest below in 1982, letting it run through March 2020 to see the recent major drawdown:

As we might expect, the 60/40 portfolio delivered the greatest risk-adjusted return (Sharpe) and had the lowest volatility and smallest drawdown. But let's explore this comparison in a little more detail.

60/40 vs. 70/30 vs. 80/20 – Choosing an Asset Allocation

This is the classic stocks/bonds asset allocation question, to which there's no simple answer. Recall that past results do not indicate future performance. That said, it's usually the best data we have to act on. Specifically though, we're interested in how different assets interact relative to each other in order to optimize the portfolio as a whole, which is why one aims to diversify their portfolio in the first place. Historical data on that aspect is a little more reliable than performance chasing.

On average, stocks and bonds have historically had a fairly reliable uncorrelation, which is why they're the first diversifier of choice, and is why portfolios like 60/40, 70/30, and 80/20 are household names. Thankfully, while past returns don't indicate future returns, past volatility is correlated with future volatility. A portfolio with any allocation to an uncorrelated asset – especially bonds – should invariably have lower volatility, and lower risk, than a portfolio of 100% stocks.

Risk Tolerance

As I said earlier, my general rule of thumb is to use your age minus 20 for your bond allocation, moving more into bonds as you near retirement. This can obviously differ based on one's personal risk tolerance.

Larry Swedroe suggests that choosing an asset allocation is investing based on one's “ability, willingness and need to take risk.” Ability refers to time horizon, need for liquidity, income, and flexibility. Willingness refers to the emotional and psychological factors; what allocation will allow you to sleep easy at night? I maintain that it is perfectly reasonable to adopt what is seen as a more “conservative” allocation such as 60/40 if it allows you to sleep better than a 100/0 portfolio, especially during market turmoil. Need refers to the investor's required rate of return to achieve their financial goals, usually a specific amount of money needed to retire. Once you hit that amount, you no longer have a need to assume additional risk.

Obviously, a young investor will likely naturally have more ability and willingness to take on additional risk, hence the popular mantra of “go 100% stocks for a while.” That's where my general suggestion of age minus 20 fits in, allowing you to slide to a more conservative allocation as time goes on. This is because accumulation is more important for the young investor and capital preservation becomes increasingly important as you near retirement. Using that suggestion, a retiree at age 60 has a stocks/bonds allocation of 60/40.

This is also why I say a one-size-fits-most allocation is 80/20, assuming an average age along that spectrum of 40 years old. Using my math, a 30-year-old investor would have 10% in bonds. That 10% isn't going to make or break the portfolio, but it may affect the overall portfolio's volatility – and the subsequent emotional impact of drawdowns – considerably.

William Bernstein suggests that one can evaluate their risk tolerance based on how they reacted to the Subprime Mortgage Crisis of 2008:

- Sold: low risk tolerance

- Held steady: moderate risk tolerance

- Bought more: high risk tolerance

- Bought more and hoped for further declines: very high risk tolerance

Vanguard has a questionnaire tool here to help you determine your personal risk tolerance to then inform your asset allocation, but while it may be a useful exercise, it's still only one piece of the risk tolerance puzzle and doesn't factor in things like current mood, current market sentiment, external influence etc. Be mindful of these things and try to be as objective as possible. The behavioral aspect of investing is very real and can have significant consequences. Are you going to panic sell if your portfolio value drops by 37% like it did for an S&P 500 index investor in 2008 during the Global Financial Crisis? Assess your tolerance for risk carefully and choose an asset allocation that will allow you to “stay the course,” as Bogle said.

Also acknowledge and account for cognitive biases such as loss aversion, the principle that humans are generally more sensitive to losses than to gains, suggesting we do more to avoid losses than to acquire gains.

Vanguard also has a useful page showing historical returns and risk metrics for different asset allocations that may help your decision process. Keep in mind the same performance seen on that page may not carry into the future.

Bond Duration

Hopefully you're starting to see that risk tolerance and asset allocation are not simple topics.

Another piece of the puzzle when comparing 60/40 vs. 70/30 vs. 80/20, etc., is bond duration. Just as a young investor is likely able and willing to take on more risk with a lower bond allocation, so too are they able to utilize longer-term bonds that are more volatile.

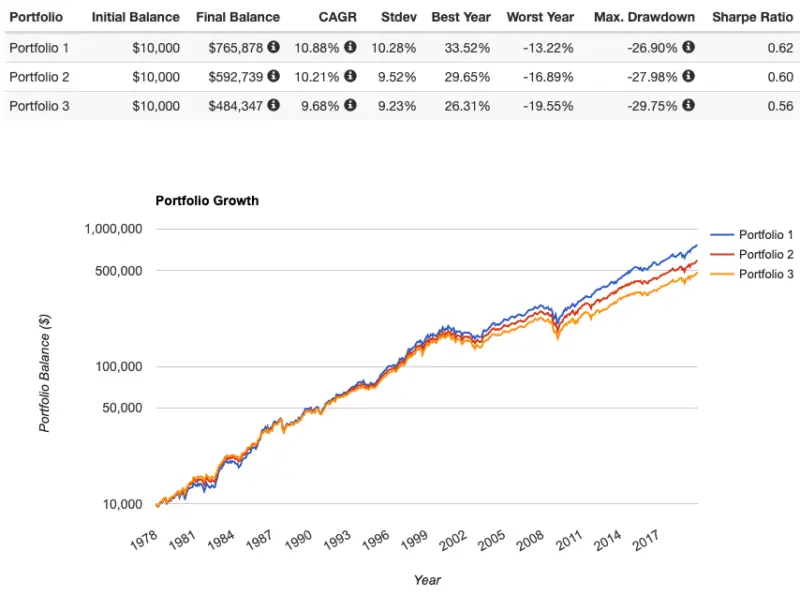

Many shy away from long-term bonds due to their inherent high volatility without realizing that you precisely need that extra volatility to effectively counteract the downward movement of stocks, as stocks tend to be more volatile than even long-term bonds, especially if you have a low allocation to bonds. To illustrate this, let's look historically at a 60/40 portfolio that uses long-term bonds vs. one that uses intermediate-term bonds vs. one that uses short-term bonds from 1978 through 2019:

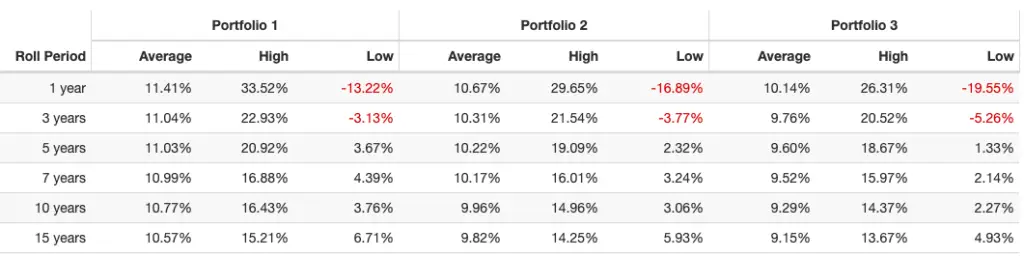

Notice the higher general and risk-adjusted return (Sharpe) – and smaller max drawdown – for Portfolio 1 with long-term bonds, with only slightly more volatility than its intermediate-term and short-term counterparts. Here are the rolling returns over that time period:

The key takeaway to remember here is we're not concerned how an asset like long-term bonds performs in isolation; we're interested in its contribution and interaction in the portfolio as a whole. Again, though it may seem counterintuitive, long-term bonds are able to reduce portfolio drawdowns and deliver higher risk-adjusted returns precisely because of their higher volatility. This is an instance where 2 wrongs do indeed make a right: 2 highly volatile assets produce the portfolio with the highest risk-adjusted return and smallest drawdowns. At least this has been true historically.

Does this mean your entire bond holding should be long-term bonds? Probably not. A general rule of thumb is to try to match bond duration to your investing horizon. We also don't know for sure that the stocks/bonds uncorrelation will persist. I usually say that a one-size-fits-most duration for a bond-heavy portfolio is intermediate-term treasury bonds. For the sake of simplicity and a one-size-fits-most approach in this post, that's the duration I've chosen for the 40% bond holding, which, like we looked at earlier with bond convexity, should be suitable for any interest rate environment.

Realize too though that you may very well have a longer retirement than you expect. Your investment portfolio doesn't simply cease at age 60. For that reason, I like the idea proposed on the Bogleheads forum of putting the “first 20%” of your bonds in long-term bonds, at least until retirement. This means a 90/10 portfolio and an 80/20 portfolio would have entirely long-term bonds. A 70/30 would have 20% long-term bonds and 10% intermediate-term bonds. And so on.

60/40 Portfolio Returns by Year

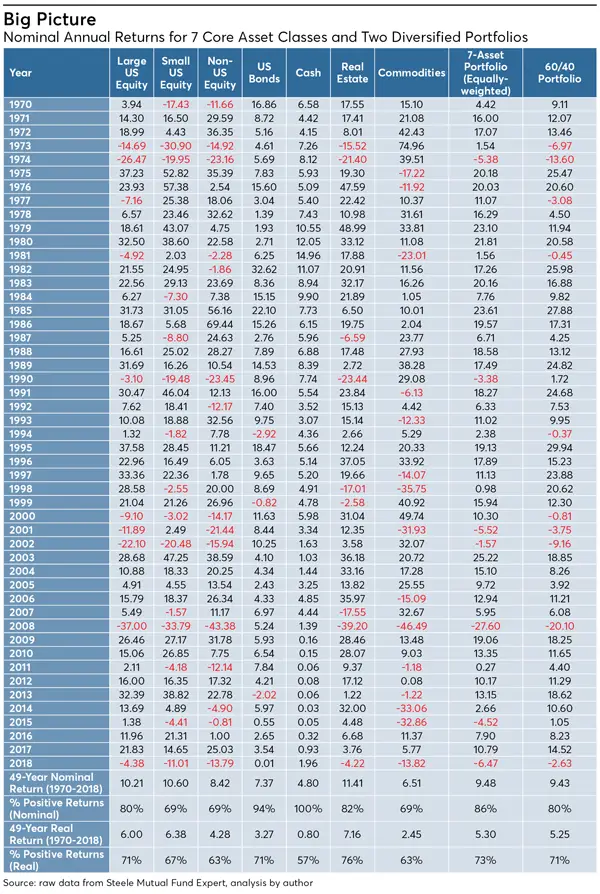

The chart below shows the returns by year for the 60/40 portfolio compared to asset classes and the S&P 500 index for the period 1970 through 2018:

Here are the returns of a 60/40 portfolio in recent years. Far from “dead” if you ask me:

2019: +21%

2020: +16%

60/40 Portfolio ETF Pie for M1 Finance

M1 Finance is a great choice of broker to implement the 60/40 Portfolio because it makes regular rebalancing seamless and easy, has zero transaction fees, and incorporates dynamic rebalancing for new deposits. I wrote a comprehensive review of M1 Finance here.

Using entirely low-cost Vanguard funds, we can construct the 60/40 Portfolio pie like this:

- VTI – 60%

- VGIT – 40%

You can add the 60/40 Portfolio pie to your portfolio on M1 Finance by clicking this link and then clicking “Invest in this pie.” Investors outside the U.S. can use eToro.

Taking the 60/40 Portfolio International

No one ever said the 60/40 portfolio can only contain two funds. On the equity side, you could choose to go 80/20 with U.S. and ex-U.S. stocks if you want to. To keep things simple here, though, we can simply replace VTI with VT, Vanguard's Total World Stock Market fund. That fund contains about 60% U.S. stocks at current global market weights.

Our global 60/40 portfolio then becomes:

- 60% VT

- 40% VGIT

You can add this global 60/40 Portfolio pie to your portfolio on M1 Finance by clicking this link and then clicking “Invest in this portfolio.”

Canadians can find the above ETFs on Questrade or Interactive Brokers. Investors outside North America can use Interactive Brokers.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

What do you think of the 60/40 Portfolio? Let me know in the comments.

Disclosure: I am long VTI in my own portfolio.

Interested in more Lazy Portfolios? See the full list here.

Disclaimer: While I love diving into investing-related data and playing around with backtests, this is not financial advice, investing advice, or tax advice. The information on this website is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only. Investment products discussed (ETFs, mutual funds, etc.) are for illustrative purposes only. It is not a research report. It is not a recommendation to buy, sell, or otherwise transact in any of the products mentioned. I always attempt to ensure the accuracy of information presented but that accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Do your own due diligence. I mention M1 Finance a lot around here. M1 does not provide investment advice, and this is not an offer or solicitation of an offer, or advice to buy or sell any security, and you are encouraged to consult your personal investment, legal, and tax advisors. Hypothetical examples used, such as historical backtests, do not reflect any specific investments, are for illustrative purposes only, and should not be considered an offer to buy or sell any products. All investing involves risk, including the risk of losing the money you invest. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Opinions are my own and do not represent those of other parties mentioned. Read my lengthier disclaimer here.

Are you nearing or in retirement? Use my link here to get a free holistic financial plan and to take advantage of 25% exclusive savings on financial planning and wealth management services from fiduciary advisors at Retirable to manage your savings, spend smarter, and navigate key decisions.

Thank you for a great article. Can’t stocks and bonds go down simultaneously because they’re both in a bubble? Stocks are expensive if we look at historic P/E. Bonds, particularly medium and long term, are expensive because interest rates are hystoricly the lowest. I’m not suggesting interest rates may go up significantly, but they’re now going up, so both stocks and bonds are falling. The correlation does not seem to be negative anymore. Can it so be that the convexity is a matter of the past? It worked for so long, but maybe this time is indeed different? Did you try tactic bond allocation based on yields rather than age, e.g. higher yield would support more allocation to bonds?

Anything is possible. I don’t try to time the market. The environment may warrant looking into other diversifiers like gold and put options. Speaking of bonds, though, if the investor matches duration to the investing horizon, they should be indifferent to interest rate changes. The long-term investor holding for a period greater than the average bond duration should want interest rates to go up. Remember we also simply care about imperfect correlation most of the time, with negative correlation during crashes.

Do you think a combination of total bond fund and

Long term bond help with the Dusted risk?

Let’s say like in a 20% band and 5% in long term in a 75/25 asset allocation

Not sure what you mean by “Dusted risk.” I only use treasury bonds.

Very nice explanation of bond convexity. I’d question your using 1978 as a starting point to examine the performance of a portfolio of stocks and long term bonds. That pretty much coincides with a huge bull market in bonds. I’d like to see data going back to 1926. That would give a clearer picture. Larry Swedroe says that bonds longer than a 10 year term give you more risk than return, which is why he uses 10 year bond ladders or intermediate term bond funds, so avoiding long term bonds altogether. I think, apart from the last 40 bond bull market, that is the best choice. I see you are doing that with your own portfolios.

Thanks! All credit to Tyler from Portfolio Charts on the bond convexity topic. 1978 just happened to be as far back as that tool could go, which is right around when monetary policy fundamentally changed with Volcker.

In today’s market, what Bonds would you use for a 60-40 Portfolio?

VGSH appears to be doing better than BND?

Thanks

Would depend on time horizon, to which duration should be matched. I like treasuries over total bond market.

Thanks again for a great article.

One more question. Why would long-term yields go down in the times of market crashes (pushing the long-term treasuries higher and saving the 60/40 portfolio). I don’t believe in ‘smart money’ moving to ‘safe haven’. Why would they? The recession/bear market now would imply higher yields in the future, not lower. Is this all due to Markowitz and the Fed buying? Or there’s something else I’m missing?

The flight to safety behavior of treasury bonds is well documented. Yields must go down when prices go up, and vice versa, as they are simply two sides of the same coin.

(Tried to leave a comment earlier but it seems to have gotten lost – trying again here; apologies if it ends up a duplicate.)

I previously was sold on the idea that adding bonds to a long-term portfolio makes sense – backtests for the last few years/decades e.g. in Portfolio Visualizer show that adding bonds improves risk-adjusted returns; one way to take advantage of that is adding a bit of leverage (e.g. with NTSX). So far so good.

But after reading https://edrempel.com/high-risk-of-bonds/ and other sources, I’m not so sure anymore. When looking back further (pre-1980), there were multi-decade periods with negative real returns on bonds. The same is not true for stocks. (According to “Stocks for the Long Run”, the longest period [within the last ~200 years] with zero real returns from stocks [US, total market] was 17 years.)

So it seems that at least for bonds, “only” looking at performance since ~1980 suffers from recency bias. This period appears to have been exceptionally good for bond returns, considering that bond yield peaked above 15% in 1981 and has dropped ever since to <2% today. Considering this, mathematically the only way for bonds to show similar total returns in the next few years/decades would be if yields turn significantly negative. That seems implausible. So in other words, potential upside for bonds is very small (assuming interest rates won't go much below zero) and downside (rising interest rates) is big.

If interest rates stay flat, total bond return is their current yield (about 2% for long-term bonds). That's about zero real return assuming 2% inflation. If yields rise, total return will be worse. So it seems the optimistic outcome of buying long-term bonds today (for purposes of adding to a long-term portfolio) is zero real return… Because of this I'm struggling to see arguments for buying long-term bonds at current yields, as a retail investor.

I can still see uses for bonds for shorter-term purposes, mainly to store cash. But long-term bonds don't make sense to me right now. Curious what you think.

Johannes, thanks for the thoughtful comment. This one and the first one got thrown in the spam folder initially.

I think I addressed all your points in this section here. I need to add that list to this 60/40 post.

Haven’t read your link yet but I’ll check it out. In short, yes I’d agree bonds in isolation don’t make much sense right now, but we’re talking about within a diversified portfolio alongside stocks, yes U.S. monetary policy fundamentally shifted with Volcker in 1982 and I don’t think we’ll return to the ways before then, and yes we’d expect lower future returns for bonds at current yields but that doesn’t mean they’re not still doing their job of reducing volatility and risk. But in general I’d also agree that young investors with a long time horizon should go 100% stocks for a while, like I pointed out in my post on asset allocation. Short-term bonds are also a decent inflation hedge.

Hi John,

If I’m understanding correctly, the argument here, and in the longer Portfolio Charts article, is that bonds, especially long term bonds, shouldn’t be feared because rates are low due to the concept of bond convexity, the inverse relationship between bond price and interest rates, and the fact that interest rates have declined without reversion to the mean for a long time.

We often hear things like “interest rates have nowhere to go but up” and therefore bonds, especially long term bonds, are risky. However, the above facts about bonds don’t seem to negate that idea, unless I’m not understanding. Seems to me that a portfolio heavy in long term bonds (i.e. All Weather, Permanent Portfolio) has benefited tremendously from the bond bull market and quantitative easing but also has significant interest rate risk and if rates were to increase, these portfolios would take a hit. I understand that rates could go negative, which would benefit long term bonds, but I think that is unlikely.

So my question is, why shouldn’t a long term bond-heavy portfolio be feared? Seems like the prudent thing to do may be to use a barbell approach mixing long and short term bonds or possibly to overweight short term bonds. What reason is there to justify holding a large allocation to long term bonds if the expectation is that rates will not go lower them they are now?

Thanks.

Your understanding is correct.

Just because rates are low or zero does not automatically mean they will go up.

Even if rates do go up, a “normal” rise in rates is priced in. A rapid rise in rates would be bad for bonds.

I’ve never said a portfolio heavy in long bonds – which I’d define that as >50% long bonds – is a good idea, which would obviously unnecessarily expose the investor to interest rate risk. Yes a barbell approach – or just intermediate bonds, which is roughly the same thing – is probably the best way to go for a bond-heavy portfolio, but remember most investors are not going to have a bond-heavy portfolio to begin with.

As I’ve pointed out, we don’t know that rates won’t go lower, and long bonds still offer the lowest correlation to equities. But again, that doesn’t mean you should put over 50% of your portfolio in long bonds.

A lot of this is also highly personal based on time horizon and risk tolerance, as well as one’s view of monetary policy. An investor with a 5 year time horizon and a low risk tolerance probably shouldn’t be using any long term bonds, and an investor with a 30 year time horizon and a high risk tolerance probably shouldn’t be using short term bonds.